When Paul Kagame became Rwanda‘s president in 2000, he inherited a country that had been torn apart by a brutal genocide. To rebuild it, he had to rely on mostly uneducated guerrilla fighters and a handful of ill-trained cadres. Even the most optimistic of observers doubted his chances.

But 23 years later, the country is stable, prosperous, growing, unified and, in large part, reconciled. Social services, such as education, healthcare, housing and livestock are provided to the needy, with no distinction of ethnicity or region of origin – two forms of discrimination that characterised the governments leading up to the genocide against the Tutsi, which Kagame, as leader of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), brought to an end.

His grip on power has been nearly unassailable. What a lot of people fail or reluctantly admit is that he’s equally a brutal dictator. Since coming to power he has extended constitutional term limits, shut down the free press and clamped down on dissent. Reporters have been driven into exile, even killed; opposition figures have been imprisoned or found dead. His country has been reduced to tyranny.

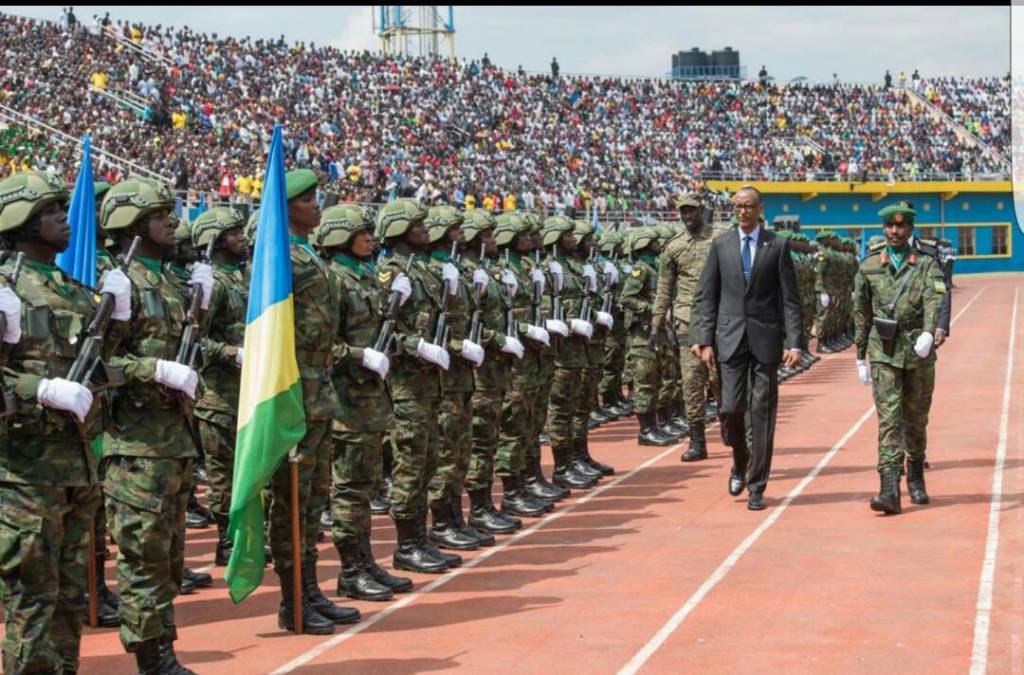

President Paul Kagame of Rwanda. Credit Photo by Ludovic Marin

But this dictator isn’t a pariah, like Vladimir Putin of Russia or Bashar al-Assad of Syria. Instead, he’s one of the West’s best and most reliable friends. Paul Kagame, since coming to power in 1994, has won his way into the West’s good graces. He’s been invited to speak — on human rights, no less — at universities such as Harvard, Yale and Oxford, and praised by prominent political leaders including Bill Clinton, Tony Blair and the former U.N. general secretary Ban Ki-moon.

It doesn’t end there. Mr. Kagame’s Western friends include FIFA, which held its annual congress at a shiny sports complex in Kigali in March, and the N.B.A., whose African Basketball League plays in Rwanda. Europe’s largest carmaker, Volkswagen, runs an assembly plant in Rwanda, and major international organizations such as the Gates Foundation and the World Economic Forum are close partners. Western donors finance a whopping 70 percent of Rwanda’s national budget.

While the criticism about his dictatorship is justified, the critics make one mistake: to imply that these freedoms were already existent in Rwanda and that Kagame simply took them away. They weren’t. Kagame and Rwandans have been working to establish them in a country that has never had them.

Born in southern Rwanda in 1957, Kagame’s parents fled the country during anti-Tutsi pogroms when he was two years old. He was raised in Rwandan communities in refugee camps in Uganda, where he observed and was a victim to the recurrent oppression visited upon his people. He later joined a Ugandan guerrilla movement, the National Resistance Army that installed Yoweri Museveni as president of Uganda.

When he returned to Rwanda as leader of the RPF, the country’s coffers had been looted, an estimated 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus had been killed, the survivors were traumatized, the killers fearful of retribution and the returnees destitute. Rwanda was a failed state by any measure.

Twenty-five years after the genocide, the wounds are slowly healing. Survivors still see Kagame as the guarantor of their existence. He pardoned the perpetrators and set the country on a journey to unity and reconciliation.

A visitor during a tour of Kigali Genocide Memorial to learn more about the history the Genocide against the Tutsi.

Kagame has been tough in his style of governance; intransigent on corruption, populism and divisive speech. Politicians with hate-charged rhetoric have consistently faced harsh sentences and lengthy prison terms. Speech is regulated to prohibit ethnic prejudice while democracy was trimmed and tailored to the peculiar predicament facing the Rwandan people. This was necessary to install a new mentality towards governance.

A new, unified country had somehow to be built with the same people – killers and their victims living side-by-side with a unity of purpose: the betterment of their village, the district, their country.

In this endeavor, Kagame was acting with the people’s mandate and within the ambit of the Rwandan constitution. His mission as Rwandan leader is first and foremost to protect the Rwandan people from genocide – by any means necessary. This mission, which is not sufficiently understood by the Western world, will probably, also be passed on to his successors for two or three generations to come.

Kagame owes much of his success to his skilled political rhetoric, an art form Rwandans call “ubwenge.” In news conferences where Rwandan journalists, aware of the risks faced by less pliant colleagues, throw him softball questions, Mr. Kagame shines. Often, his target is the West. He consistently voices an anti-imperialist message about how Europe is “violating people’s rights” and berates the West’s “superiority complex.”

This posture makes him a leading avatar of a new type of postcolonial ruler. Other populist nationalist presidents such as Erdogan of Turkey, Andrés Manuel López Obrador of Mexico and Narendra Modi of India also rally their populations behind similar sentiments, elevating themselves as world leaders no longer beholden to the West. Often at the heart of their defiant speeches are references to old crimes — massacres, genocides and expropriations committed by European empires that date back as far as the 16th century.

Such appeals work because Western leaders still offer only grudging “regrets” for such atrocities and rarely apologize, partly out of fear that their nations will have to cough up huge sums in reparations. This allows the grievances to live on. Many in former colonies still feel those past humiliations as viscerally present, manifest today in institutions that are dominated by Western interests, such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, or in international trade and aid negotiations. Postcolonial leaders such as Kagame find much popularity in their insistence that the West should atone for its history, however improbable that might be.

The BK Arena in Kigali, Rwanda where FIFA held its 73rd annual congress this year is one of the new landmarks of the Kagame administration. Credit-Wikipedia

The price of avoiding apologies, though, is that Western leaders find their moral authority diminished. Instead, they engage in placatory behaviors — offering praise and partnership, rather than condemnation. Perhaps nowhere is this dynamic clearer than in Rwanda, where Mr. Kagame’s leverage with Western leaders is particularly strong because the country’s grievances are recent. He is very adept at guilt-tripping the West and his jabs hit home hard.

Rwanda’s 1994 genocide — during which nearly one million Rwandans, many of them ethnic Tutsis, were killed — was perpetrated under the noses of United Nations peacekeepers, who diligently filed reports on the killings while seemingly impotent to prevent them. Although Kagame’s former ambassador to the United States and other political allies have accused him of “sparking” Rwanda’s genocide and doing little to prevent it, he has cast himself as the hero who ended it.

International analysts and champions of democracy have not embraced Kagame’s atypical approach, often assessing Rwandan politics through a Western lens and thus missing the complexities of governing post-genocide.

As a result, they may have missed what is arguably the most edifying case study in national transformation of the last 25 years.

Rwandan mothers receive ante and post-natal healthcare and maternal mortality ratios in the country decreased by 77 percent between 2000 and 2013. New-borns are vaccinated. The city is clean and people can walk safely at night. Since 2019, ministers no longer require personal security details. “Your security will be guaranteed like that of other Rwandan citizens,” they were told. The progress the country has made under his watch is visible.

Rwandair the national air carrier of Rwanda is amongst the top 10 airlines on the continent. Credit-SM Africa

A lot of outsiders seem concerned that Kagame has not groomed a successor, and although there are no crown princes in Rwanda, the president has chosen to groom thousands of young men and young women, in particular, to lead the country into the future. The average age of his cabinet is 40. Women make up 50 percent of the cabinet, 61.5 percent of the parliament and 50 percent of Supreme Court judges.

In 2018, Kagame chaired the African Union, championing potentially game-changing initiatives such as the Continental Free Trade Area (CFTA), which was signed in the Rwandan capital, Kigali.

President Kagame and Commander-in-Chief inspecting his troops on Liberation Day. Credit- Chronicles

Of course, major challenges remain. In 2017, the unemployment rate was 16.7 percent and the youth unemployment rate 21 percent. But Kagame is betting on the country’s MICE (Meetings, Incentives, Conferences and Exhibitions) strategy and information communications technology and off-farm employment opportunities to absorb the 250,000 young people who enter the job market each year. The bookmakers are still out, but with Rwanda’s economy expanding by 8.6 percent in 2018, the county rated the second-best place to do business in Africa and it having soared up the human development index, the indicators are looking promising.