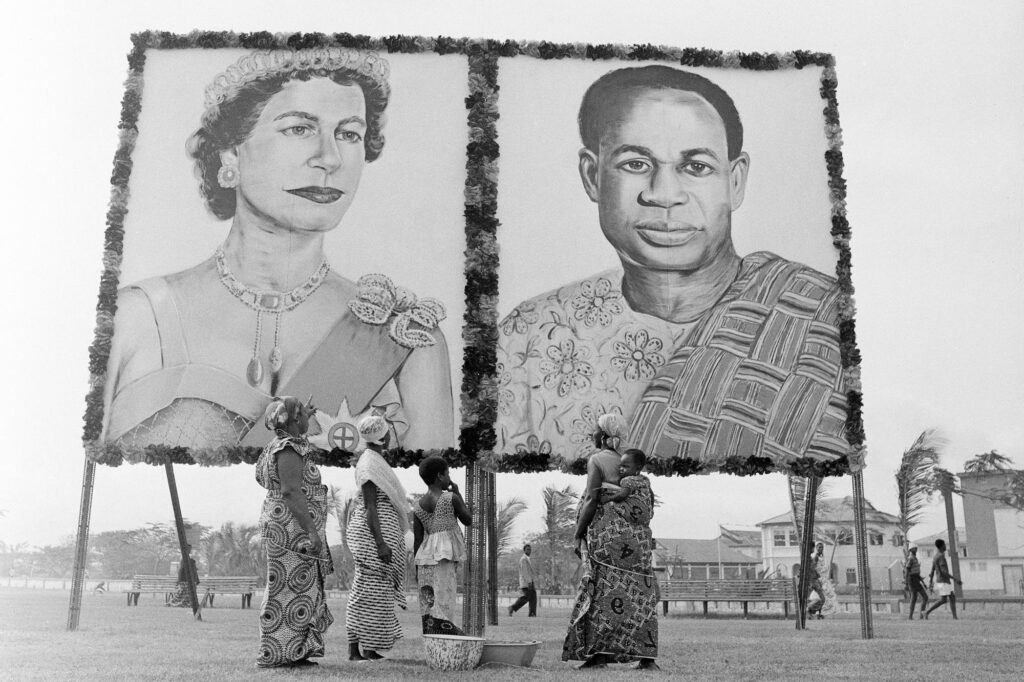

From Kenya to Nigeria to South Africa, the death of Queen Elizabeth II prompted an outpouring of condolences from African heads of state, who have been praising her as an “extraordinary” leader and sharing memories of her frequent visits to the continent during her 70-year reign.

Upon ascending the throne in 1952, Queen Elizabeth II inherited millions of subjects around the world, many of them unwilling. In the British Empire’s former colonies, her passing has brought mixed and complicated feelings, including anger.

Beyond official condolences praising the queen’s longevity and service, there is deep seated bitterness about the past in Africa, the Caribbean and other Commonwealth nations. People are talking about the legacies of colonialism, from slavery to corporal punishment in African schools to looted artifacts held in various British institutions. For many, the queen represented all of that during her years on the throne.

In the reality of a younger generation of Africans who are growing up in a post-colonial world, some have lamented that the queen never faced up to the grim aftermath of colonialism on the African continent, or issued an official apology. This is why they wanted to use the moment to recall the oppression and horrors their parents and grandparents endured in the name of the Crown, and to urge for the return of numerous crown jewels taken from the continent.

The reactions from people all over the continent and the Caribbean have clearly been mixed. While some have shown some form of sympathy for the Queen’s passing, a good majority have expressed a deep seated anger at the royal family for what they term unforgivable crimes against the black race.

The official condolence messages from leaders and officials on the continent have almost unanimously praised the Queen’s reign, record of duty and long-standing engagement with the continent. In Uganda, where she made her last visit to Africa for the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in 2007, parliament held a special sitting to honor her.

One legacy of British colonial rule is that Nigeria is home to one of the world’s biggest Anglican communions. The Church of Nigeria held a Remembrance service for Queen Elizabeth in Abuja, where its head, Most Reverend Ali Buba Lamido, said that as the head of the Church of England, the Queen was also important for Nigeria’s Anglicans.

Reporters who attended the ceremony said the mood was somber but that many did not want to go on the record to offer their condolences – perhaps a reflection of the heated debate over the British Monarchy’s legacy in Africa.

In Kenya, somewhere in the Mathare informal settlement, 32-year-old Douglas Mwangi thinks the Queen should be celebrated for her work with the Commonwealth, which she led for 70 years. It is a loose organization of 56 countries, mostly former British colonies.

In 2018, Douglas visited Buckingham Palace to receive the Queen’s Young Leaders Award from the Monarch. He receives training and funding from the Queen’s Commonwealth Trust that helps his organization support young people with ICT skills. He says the trust has helped over 14,000 people in Mathare since 2014.

Not all feel the same way. Mr Njau, a businessman, says he does not see how the Commonwealth helps him: “It is crazy that we’re even in that wealth – whatever that Commonwealth is – I have tried to research how we benefit as Kenyans by being in the Commonwealth and it looks like it just benefits a few leaders, a few people.”

“This commonwealth of nations, that wealth belongs to England. That wealth is something never shared,” said Bert Samuels, a member of the National Council on Reparations in Jamaica. He went further by saying “Her death represents an end of an era and I think with it, so should the era of commonwealth association.

Elizabeth’s reign saw the hard-won independence of African countries from Ghana to Zimbabwe, along with a string of Caribbean islands and nations along the edge of the Arabian Peninsula.

The debate over how Africans should view the queen went viral when Uju Anya, a Nigeria-born professor at Carnegie Mellon University, posted a tweet in which she wished the queen “excruciating” pain on her deathbed for overseeing a “thieving raping genocidal empire.” When criticism came — including from her own university and Jeff Bezos, the billionaire founder of Amazon — Ms. Anya doubled down.

“If anyone expects me to express anything but disdain for the monarch,” she wrote, “you can keep wishing upon a star.” Her original tweet was removed by Twitter for violating the platform’s rules.

27-year-old Naledi Mashishi, whose South African grandmother was forced to sing the God Save the Queen anthem each day at school, Queen Elizabeth will forever remain the face of the empire and its bitter legacy in Africa.

In the wake of the queen’s death, Ms. Mashishi joined a legion of young South Africans demanding the return of the diamonds that form part of the crown jewels. Cut from the Cullinan, which was discovered in South Africa in 1905 and considered the largest diamond ever found, the rare gemstones sit atop the Imperial State Crown and the Sovereign Scepter, which are both used during the coronation of the British monarch.

The stone was a gift from the Afrikaner government to King Edward VII after the South African War, also known as the Anglo-Boer War. But Black South Africans have questioned a minority government’s right to bestow as a gift a gem uncovered during a time of brutal exploitation of Black people. On her 21st birthday in 1947, the Queen made a speech from a still segregated Cape Town, pledging her service to the Commonwealth.

“I think there’s something very disingenuous about saying the queen or the current royal family have nothing to do with the past,” Ms. Mashishi said. “Meanwhile, they are still happily wearing these stolen jewels.” But with the queen’s passing, observers say that tough conversations about the empire’s past actions in Africa will only continue to gain steam.

“Its way more than the diamonds,” said Lebohang Pheko, a political economist and a senior researcher at the South African think tank, Trade Collective. “There are not going to be easy conversations around this anymore.”

Karen Attiah, a Ghanaian-Nigerian born columnist for The Washington Post, wrote: “Black and brown people around the world who were subject to horrendous cruelties and economic deprivation under British colonialism are allowed to have feelings about Queen Elizabeth. After all, they were her ‘subjects’ too.” “Even under her reign, there was the Mau Mau rebellion of Kenya when the country was still under British rule, which they violently crushed, putting Kenyans into concentration camps, which to this day, the survivors and the descendants are seeking damages from the U.K. for those atrocities.

The reality remains, that for many, the British monarchy represents something far worse than royal paraphernalia. The British Crown, for those unfortunate enough to have lived under British rule, instead came to represent enslavement, violence, land theft, and destruction of communities. As a result, the perception of the British monarchy in its former colonies became significantly blighted. The institution’s fiercest critics assert that colonialism, class privilege, and economic inequality form the basis of what the monarchy represents, with many around the world now reassessing its role in light of the Queen’s death.

Moses Ochonu, a professor of African History at Vanderbilt University in the United States, staunchly opposes the Commonwealth. To him, the Queen’s death has brought attention to “unfinished colonial business”. Scathing in his assessment of the British monarchy, he states that “there is a sense in which Britain has never fully accounted for its crimes”, thus clearly expressing contempt for an institution mired in colonial atrocities. Dr Ranjeet Baral, a doctor based in Kathmandu in Nepal, agrees with Ochonu’s claims, himself stating that “Britain must accept reality and not try to cling onto something which has lost its value and take the initiative and dispense of the Commonwealth with dignity”, arguing that the Commonwealth has long exceeded its sell-by date.

Though proponents of the Commonwealth take a rather different view. Whilst not denying its obvious colonial links, its supporters argue that the group is held together through shared traditions, experiences, as well as economic interests. For some, the Commonwealth has moved on from being overtly colonial, as membership to the club is in no way contingent on recognising the British monarch as head of state. Of the 54 members of the Commonwealth, 36 are republics, including India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, whereas others, such as Brunei, Lesotho, Malaysia, Eswatini and Tonga, all have their own monarchs. Besides, nations don’t even require any ties to the British Empire to join. Gabon and Togo – two former French colonies in West Africa – joined the group in 2022, perhaps indicating the supposed economic and political benefits of joining the bloc.

The internal divisions within the bloc are clear enough though, with calls to sever ties with the British Crown becoming increasingly difficult to ignore. In November last year, the Caribbean Island nation of Barbados became a republic, breaking decades of ties to the British Monarchy, highlighting that a precedent for departure has already been set.

What Africa thinks of King Charles

The laws and traditions that govern Britain’s constitutional monarchy dictate that the sovereign must stay out of partisan politics, but Charles has spent much of his adult life speaking out on issues that are important to him, particularly the environment.

His words have caused friction with politicians and business leaders who accused the then-Prince of Wales of meddling in issues on which he should have remained silent. The question is whether Charles will follow his mother’s example and muffle his personal opinions now that he is king, or use his new platform to reach a broader audience.

“My life will, of course, change as I take up my new responsibilities,” Charles said. “It will no longer be possible for me to give so much of my time and energy to the charities and issues for which I care so deeply. But I know this important work will go on in the trusted hands of others.”

The king has been clear that he intends to slim down the monarchy, limiting the number of working royals and reducing the expense of supporting them.

When asked by the press what he made of the criticism of the late queen, Ghana’s former leader John Kufuor said he wasn’t going to “criticize people for what they think. I am telling you what I think. The queen, I am not going to visit her with the sins of her fathers from ancient times.”

He said the world had progressed beyond the atrocities of the past and what is needed now is a spirit of “interdependence, centering humanity above all as the reason why there shouldn’t be animosity towards the late monarch.

With the death of the queen, her eldest son Charles III, the former Prince of Wales, has been leading the country in mourning as the new king. He also assumes the role as head of state for 14 Commonwealth realms.

“I would expect him to be mindful of the implications and challenges of the responsibilities that have been thrust on him as king. He should set a good example of his mother,” Kufuor said of the new monarch.

Despite the complicated history of the monarchy, to many, Queen Elizabeth II was a beloved monarch — evidenced by the people all over the world who made their way to England to pay their respects to the queen who always said she was merely a humble servant.

The debate that has followed the Queen’s death on the continent is a clear sign that there are many unhealed wounds and trauma from colonial times and many feel now is the moment for Britain and its new King to have honest conversations with Africans about how to heal this painful past.