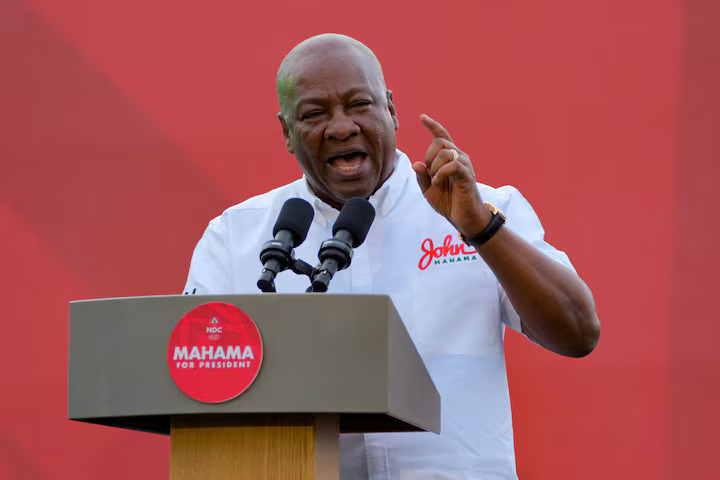

Ghana’s incoming president, John Mahama has vowed to “reset” the nation on a path “for good governance and accountability. Credit-CNN

When Ghana gained Independence in 1957, one of its founding fathers Osagyefo Kwame Nkrumah asserted that “the independence of Ghana would be meaningless unless it was tied to the total liberation of Africa”. The foremost Pan-Africanist went on to lead Ghana in playing a central role in the decolonisation process and liberation struggles across Africa.

Nkrumah in his usual impressive use of words with such calm precision became the motivation for Africa’s long move from the decolonisation era, and this generation of Ghanaians have carried on this enviable bequest – this time becoming a leading light in addressing Africa’s challenge of peaceful democratic transitions, by demonstrating this is possible, over and over again.

Self-evidently, today, the country has earned its pride of place in the global world order, and is celebrated as one of the models in the Global South, for economic stability, democratisation, and peaceful transitions. Undoubtedly, the West African country keeps strengthening her institutions and enacting enabling legislations that would ensure this legacy of peaceful transitions endure.

From the foregoing, it is crystal clear that the replica of America’s 2024 general elections in Ghana was yet another landmark event in the continent of Africa. The American 2024 presidential election which marked a historic and improbable comeback for Donald Trump, who left office in 2021 after failing to overturn the 2020 election results. The only difference is that as a sitting President, John Dramani Mahama did not attempt Trump’s malady of 2020.

For the records, John Dramani Mahama (JDM) is set to return as Ghana’s president after his main rival accepted defeat. The NPP’s defeat, by one of the largest margins in recent history, was seen as punishment for the outgoing government’s performance. Commentators surmised that Ghanaians had been sufficiently displeased by the state of affairs to instead re-elect Mahama, whom they had kicked out unceremoniously in 2016 – the first time an incumbent had been unseated.

The former president’s comeback on his third attempt makes him the first person in the West African state to win two non-consecutive terms. The election followed a pattern voters have studiously kept in place since the return to multiparty democracy in 1992: every government that has served two four-year terms has been replaced by the opposition.

Economic hardship was a major factor: at one point, inflation was as high as 50% and the cedi, Ghana’s official currency plummeted to historic lows while the number of taxes increased. A banking sector purge that was hailed by economists but led to thousands of job losses also angered voters, as did a bloated government in which several relatives of the president and ruling party members served.

Since Ghana’s independence in 1957, it has received bailouts from the International Monetary Fund 17 times, according to a report from the African studies department of the University of Aberdeen.

So a sure sign that the government was on its way out was its handling of talks with the IMF for a three-year, $3bn rescue package as the country repeatedly defaulted on foreign debt obligations. It was preceded by the government not telling the truth to Ghanaians in the sense that when the president said the government was not going to embark on any IMF journey, the finance minister came to make an announcement that they have taken the decision to go.

That cost the government a lot of goodwill. Pensioners demonstrated in a series of protests in the capital in 2023 about delayed benefits resulting from a controversial debt swap programme introduced as part of conditions for accessing the IMF facility.

All of this largely contributed to apathy in the elections, experts say.

In the past two elections, Ghana’s election turnout rates have exceeded 70%. The recent one which was conducted in 2020 had a turnout rate of about 79%, but this one fell to 60.9%. In the Ashanti region – the stronghold of the NPP – apathy was so high that the turnout rate was around 35%.

Beyond that, witnesses and experts say the NDC had learned from its previous defeats and enacted a number of strategies to win the election. One of them was the mobilisation of its supporters to be vigilant and monitor the process to avoid any tampering with ballots.

John Dramani Mahama, who was president from 2012-2017, won re-election at the third attempt after falling short in 2016 and 2020 elections.

Although the election was generally peaceful, two people were shot dead on Saturday in separate incidents. The electoral commission office in the northern town of Damongo was also destroyed, allegedly by NDC supporters angry at the delays in announcing the results.

Mahama, 65, previously led Ghana from 2012 until 2017, when he was replaced by Akufo-Addo. Mahama also lost the 2020 election so this victory represents a stunning comeback.

Mahama’s NDC and the governing New Patriotic Party (NPP) have alternated in power since the return of multi-party politics to Ghana in 1992. No party has ever won more than two consecutive terms in power – a trend that looks set to continue. His previous time in office was marred by an ailing economy, frequent power-cuts and corruption scandals. However, Ghanaians hope it will be different this time round.

During his campaign, Mahama promised to transform Ghana into a 24-hour economy, reset the country and sought to appeal to young Ghanaians as the candidate who could get the country out of the economic crisis in which it has been engulfed for years. Amongst other measures, Mr. Mahama has promised to create more jobs; launch a $10 billion infrastructure development plan; scrap university fees for first-year students; and provide free primary health care.

John Dramani Mahama, 66, had a privileged upbringing in the country’s historically marginalized north. His father was a member of Parliament in the early 1960s. A lawmaker himself in the 2000s, Mr. Mahama was Ghana’s vice president in 2012 when the country’s leader, John Evans Atta Mills, died. Mahama then won the 2012 presidential contest, but he became deeply unpopular amid economic woes and recurring power shortages that earned him the nickname Mr. “Off-On” — or “Dum-sor,” in the local Twi language. He lost to Mr. Addo in 2016 and 2020.

Supporters of John Mahama celebrate in Accra. Credit-AFP

Analysts say there is little ideological difference between Mr. Mahama and Mr. Buwami — and their parties. While both are from Ghana’s north, Mr. Mahama is Christian and Mr. Bawumia is Muslim.

The election in Ghana comes months after another West African country, Senegal, also staged a peaceful presidential contest, in the region that in recent years has otherwise been stained by coups, delayed elections and aging presidents clinging to power despite constitutional limits.

As Mahama prepares to take office as Ghana’s new president on January 7, he will need to work towards achieving macroeconomic stability while boosting the competitiveness of the country’s economy. He will also need to focus on increasing transparency and removing corporate subsidies—whether public or private—rather than removing household subsidies, which many rely on for subsistence.