Children wave African and Chinese flags during a reception at the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (Focac) in Beijing on 4 September, 2024. Credit- AP Photo

China has unveiled a bold new strategy to deepen its influence in Africa – with mixed reactions over whether the continent will truly benefit from it. At the close of the latest China-Africa cooperation forum, Beijing presented an elaborate proposal to boost African development while securing its own strategic foothold.

The Beijing Action Plan is China’s blueprint for the next three years, committing a staggering €46 billion in aid, investments and credit lines.

Building on the Dakar Action Plan – signed in the Senegalese capital in 2021 to strengthen cooperation in trade, infrastructure and development – the new deal promises African countries €27 billion in credit, €10 billion in assistance and €9 billion in direct investment from Chinese companies.

Its unveiling, made during the ninth Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (Focac) held last week in Beijing, marks a key moment in the strengthening relationship between the two regions.

But while the numbers sound promising, questions linger about the true impact on Africa.

A lot of observers and analysts feel that monitoring these commitments will be difficult and there’s no certainty if or when these targets will be met.

There are also concerns that a lack of clear oversight and evaluation is one of Focac’s biggest weaknesses.

Beyond financial aid, China’s strategy this time extends into new territory: political and security cooperation.

The plan also includes promises of training African military forces, participating in peacekeeping efforts and combatting terrorism.

Beijing has also expressed a desire to foster “exchanges between political parties”, generating concern that China may be encouraging African governments to adopt elements of its own authoritarian model.

At the same time, China’s so-called Global Security Initiative promotes an alternative to the US-backed “rules-based order” by emphasising territorial sovereignty and noninterference.

This initiative, which advocates for less external influence in African countries, resonates particularly in regions frustrated by Western interference.

The Beijing Declaration issued at the end of the forum went even further – tapping into anti-colonial sentiments across the continent.

It referenced a February 2024 African Union statement on reparations, demanding that the US and other Western nations end sanctions on countries like Zimbabwe, Eritrea and Sudan.

These nations, the declaration said, “have the right to decide the future of their own country”.

In a keynote address, China’s President Xi Jinping spoke of what he described as the shared struggle of China and Africa against colonialism.

Chinese President Xi Jinping speaks at the opening ceremony of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on September 5, 2024. | Photo Credit: AP

“Modernisation is an inalienable right of all countries,” Xi said, adding that the Western approach to development had caused “immense suffering” to nations in the Global South.

“Since the end of World War II, developing nations, represented by China and African countries, have achieved independence … and have been endeavouring to redress historical injustices…”

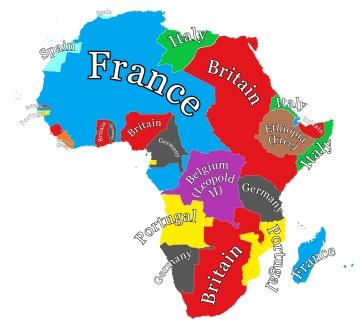

Like many African nations, parts of China were colonised in what Beijing’s propaganda calls the “century of humiliation” – referring to the period that colonial powers Portugal, Britain, Russia and Japan occupied sometimes large swaths of Chinese territory.

After the Opium Wars with London in the 1850s, China’s rulers were also forced to sign “unequal treaties” that granted Britain and other foreign powers substantial control over its trade.

China became completely free of foreign occupation only with the return of the British and Portuguese enclaves of Hong Kong and Macau in 1997 and 1999 respectively.

The Focac process is part of a longer trend that began during the Cold War with the non-aligned movement of the 1950s, when Beijing emerged as a leader of a bloc independent from both the US and the USSR.

Today China is seeking to position itself as the leader of the Global South, a catchphrase for the developing world – a group of nations often at odds with the US and its allies.

Its message of rewriting the international, US-dominated, order resonates with African nations that often feel abandoned by their traditional Western partners.

By presenting itself as an alternative, China has gained considerable influence on the continent. It worth pointing out that this partnership is all about strategy.

States don’t have friends, they only have interests. China’s engagement is as much about securing its own strategic goals as it is about helping Africa.

For African nations, China offers much-needed access to finance, infrastructure and technology.

There’s no doubt that African countries stand to gain from China in terms of easier access to finance and technology, and in terms of narrowing the infrastructure gap.

That’s why China is becoming indispensable. China has the money and the technology, and Africans need that money and technology. This is why any other discourse that does not meet the expectations of Africans will not be heard.

But, as living costs and inequality continue to rise across the continent, African governments will need to tread carefully.

Today, the traumas of colonisation and post-colonial exploitation have developed anti-French sentiment in West Africa. African streets are abuzz with demonstrations hostile to government decisions.

Anti-Western sentiment is growing, particularly toward countries like France, and this dynamic could affect how Africa engages with global powers, including China.

How the Beijing Action Plan plays out will shape the future of Africa-China relations – and reveal whether this evolving partnership will truly benefit both sides.