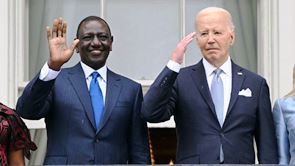

U.S. President Joe Biden recently welcomed Kenyan President William Ruto to the White House for a state visit, pledging new partnerships on technology, security and debt relief to the leader of one of Africa’s strongest democracies.

The visit of the Kenyan President presented an opportunity for President Joe Biden to demonstrate the United States commitment to Africa at a time when Washington appears to be playing catch-up in its engagement with the continent.

Current relations with other African allies are under serious strain, as strategic rivals including Russia, Iran and China have been challenging traditional areas of Western influence.

The Kenyan President’s visit also comes at a time when Kenya is preparing to deploy forces to Haiti as part of a U.N.-led effort to address the escalating security crisis in the Caribbean country.

Approximately 1,000 Kenyan police officers are set to arrive in Haiti soon, joining a multilateral security support mission aimed at quelling gang violence. Other countries expected to support Kenyan forces include the Bahamas, Barbados, Benin, Chad, and Bangladesh.

Ruto’s is the first state visit by an African president to the White House since 2008, a gesture toward the importance of a continent that is home to 1 billion people and nurtures close trade ties with China and follows state visits from the leaders of France, South Korea, Australia, India, and Japan—all increasingly important geopolitical partners.

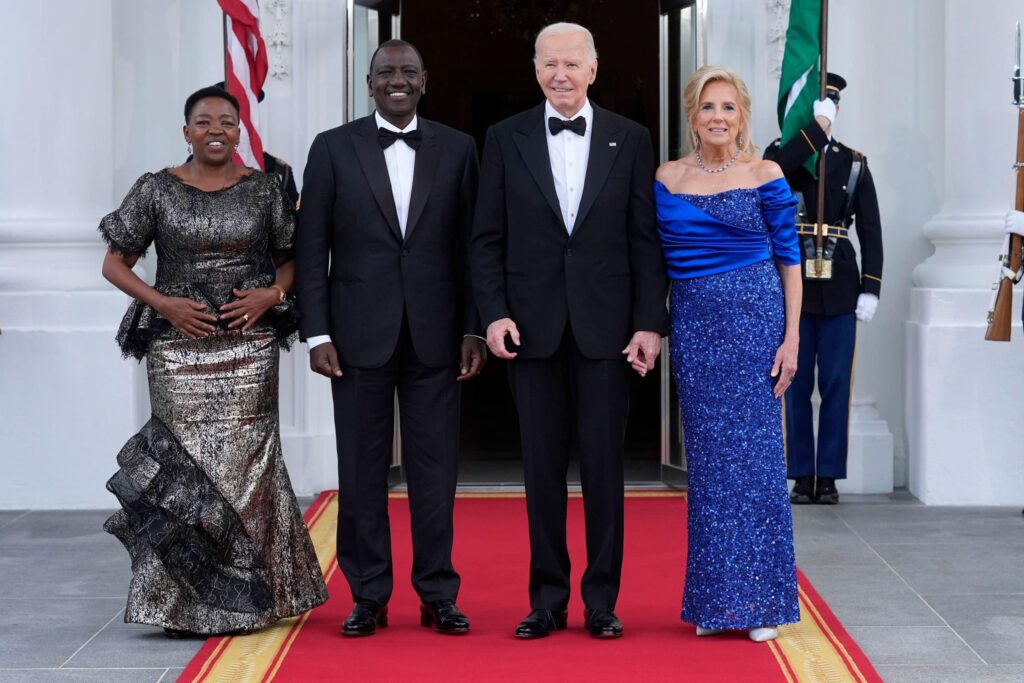

On the first day of his visit Ruto was the guest of honor at a lavish state dinner that drew a wide range of guests, from singer-songwriter Don McLean to NFL commissioner Roger Goodell, the CEOs of Walmart (WMT.N), opens new tab and Pfizer (PFE.N), opens new tab as well as former President Bill Clinton. Former President Barack Obama, whose father was Kenyan, made a brief appearance before the meal.

President Ruto’s visit does not simply represent America’s renewed commitment to the African continent, a promise President Biden made almost two years ago at the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit. Tightening U.S.-Kenya relations is also about building and safeguarding a more resilient global economy led by the United States. Investing in emerging economies like Kenya is an insurance policy against geopolitical shocks, namely from China and Russia.

In recent weeks, the focus of the insurance policy has been America’s domestic industrial strategy, specifically the Biden administration’s latest round of tariffs on selected imports from China. But the strategy is global in nature, and must be understood that way. As Biden’s top national security advisor Jake Sullivan put it in his landmark speech at the Brookings Institution last year, “it isn’t feasible or desirable to build everything domestically. Our objective is not independent isolationism —it’s resilience and security in our supply chains.”

“We may be divided by distance, but we are united by the same democratic values,” Biden said as he greeted Ruto on the South Lawn of the White House. Biden reminisced about his own visits to Kenya as a young man, hailing 60 years of diplomatic relations between the two countries after Kenya’s independence.

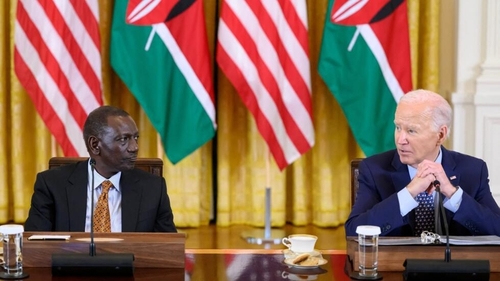

“My visit takes place at a time when democracy is perceived to be retreating worldwide,” Ruto said, standing with Biden, Vice President Kamala Harris and other cabinet officials. Earlier, he had met privately with Biden in the Oval Office.

“We agreed on the significant opportunity for the U.S. to radically recalibrate its strategy and strengthen its support for Africa,” Ruto said. Biden said he would designate Kenya as the first sub-Saharan African country to be a major non-NATO ally. Qatar, Israel and 16 other countries share that designation.

The Kenyan president arrived in the United States and visited Atlanta where he visited The King Center, met NBA legend Shaquille O’Neal, and toured Tyler Perry Studios. He then spoke with business executives in the White House on the next day. He also discussed digital inclusion in Africa with Vice President Kamala Harris at an event hosted by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

Successive U.S. governments have said they wanted to offer African countries a more sustainable and democratic alternative to relations with China and Russia, but Washington has failed to establish deep ties.

The continent’s political landscape has been upended in the past year by a spate of military coups, wars and shaky elections that have given China and Russia greater influence. Biden is hoping strengthening ties with Kenya, seen as a democratic stronghold, can help stabilize the continent and advance U.S. interests.

Building a resilient economy that can withstand geopolitical shocks cannot happen in a vacuum—reliable partners need to be part of that equation. America’s current industrial policy increasingly relies on “friendshoring” global supply chains, which means financing efforts overseas in “friendly” countries to help make strategic supply chains in the U.S. more resilient and less reliant on countries like China.

Examples of these global efforts include Biden’s Summit on Global Supply Chain Resilience, the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity, the U.S.-EU Trade and Technology Council, the Minerals Security Partnership, and the critical minerals trade agreement with Japan. But purveyors of Biden’s global economic agenda like Sullivan and U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen know the strategy cannot be limited to advanced industrial economies.

That’s where countries like Kenya come in. Emerging economies including India, Brazil, Indonesia, and Kenya are poised to contribute to the global value chain in strategic sectors like batteries for electric vehicles, chips for critical technologies, and mineral and metal mining and processing. With their human capital, natural resources, and manufacturing potential, deepening U.S.-commercial ties with emerging economies have the potential to help American companies, and the global economy, become more resilient against geopolitical uncertainty.

Tech CEO-turned U.S. Ambassador to Kenya Meg Whitman, who has led Fortune 500 companies including eBay and Hewlett Packard Enterprise, is not shy about touting Kenya’s vast insurance potential for the United States. Last month at the annual American Chamber of Commerce Business Summit in Nairobi, Ambassador Whitman made a convincing appeal to American investors about why Kenya should be their next target destination. Her selling points were in lockstep with the Biden administration’s larger economic agenda: supply chain resilience and climate-friendly economic growth.

Most critically, Kenya offers American companies opportunities to diversify their supply chains away from Asia while shrinking their carbon footprint—over 90 percent of Kenya’s power is sourced from renewable energy. Kenya, with the help of the US and other partners, also seeks to become a hub for green-powered data centers, mineral and metal processing, and green manufacturing, including producing batteries and electric vehicles. Kenya has already emerged as a leading tech market in Africa, being the continent’s largest destination for start-up financing and home to the first semiconductor manufacturer on the continent.

Kenya has just as much to gain, if not more, from its relationship with the United States. Increasing U.S. investment in Kenya will be the focus of Ruto’s visit, including the renewal of the African Growth and Opportunity Act which is set to expire in 2025 and furthering the Strategic Trade and Investment Partnership, a trade deal focused on addressing non-tariff barriers and boosting two-way trade. But while President Ruto’s affinity for the United States will be on full display this week, Kenya won’t be closing the door on business opportunities with America’s geopolitical rivals anytime soon.

From Kenya’s vantage point, the United States is an important economic and security partner. Based on sheer trade volume alone, it would seem Kenya views China, the EU, India, and the UAE that way too. Just in October, President Ruto was on his way to China, Kenya’s top overall trading partner, for an official visit to discuss Chinese investment in Kenya, the most famous projects of which include the Standard Gauge Railway, the Nairobi Expressway, and the Lapsset Corridor, all aimed at boosting connectivity and commerce across the region.

“It’s a delicate balance,” President Ruto explained to a group of Harvard Business School students in Nairobi a week before his U.S. trip, responding to a question about how Kenya balances its relationships with the United States and China. “We want to be friends to all and an enemy to none.”

A Gallup poll conducted last year found that the US had lost its soft power edge while China had gained fans. But the biggest change was Russia’s rise in popularity.

“Historically the West has seen Africa as a problem to be solved. Actors like China and Turkey, and other Arab Gulf players, they see it as an opportunity to be seized,” says Muritha Mutiga, the Africa programme director for the International Crisis Group.

So, the way in which China, Turkey and the Gulf have engaged has been welcomed, because it is seen as a long-term bet, it is seen as taking the continent seriously.”

The Biden administration points to some success in its efforts to treat Africa as a strategic partner.

A stream of high-level visits has framed the importance of Africa as “the continent of the future”, with its young fast-growing population, abundance of natural resources and increasing influence on the international stage.

American backing has helped African nations win better representation at global forums, such as the G20, IMF and World Bank, although the US has struggled to get African support for its positions on Israel’s war in Gaza, and Russia’s war with Ukraine.

The administration has also won plaudits for investing in the Lobito Corridor, a rail line snaking through Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia that will be used to transport critical raw materials.

“With that Lobito Corridor, [the Americans] decided to speak in the language that Africans understand,” says Kingsley Moghalu, a Nigerian political economist and former central bank governor.

“If you are seen to be delivering major projects that are beneficial to African economies, and to African people, then off the back of that you have leverage to talk about democracy and things like that.”

The head of the Africa Programme at the Chatham House think-tank in London, Dr Alex Vines pushes back on the perception that Western power is fading in Africa. “One African leader said to me: ‘We get tired of a Chinese buffet, we’d like to go a la carte, we want choices,’ ” he says.

“So, I do think what we’re increasingly seeing is that plenty of African countries want a bit of the United States, but they will want a bit of Russia or UAE or Turkey.”

The challenge is “patchy African leadership” with ambitious, long-term vision that can make the most of the competition.

President Ruto is seen as one of the figures who can, but all, including Niger, have options.

“There is a game of chess going on,” Dr Vines says. “There is a new scramble for Africa. The difference is that the chess board, the African continent, is alive, it’s not passive. It can suck people in and really surprise them.”