February 26, 2025 makes it 140 years since the Berlin Conference of 1884, where Western powers side-lined Africans and carved up ‘ownership’ of the continent among themselves.

This Conference in 1884 -1885 was the seminal meeting where 14 European nations and the USA met to formalise the ‘Scramble for Africa’, which directly ushered in a new era of European imperialism, resulting in the carving up of Africa into the national boundaries that by and large, we still have today. Otto von Bismarck who was the First Chancellor of Germany organized the conference at the request of King Leopold of Belgium. The ensuing age of imperialism was formalised by the General Act which was the main output of this conference, which paved the way for formal colonisation, the expansion of private concession companies, European financial institutions and the colonial violence that came with it.

It was the late 19th century and European nations were beginning to look at the African continent as a more permanent resource base for their newly growing industrial sectors.

More than the ongoing trade between the two continents that had run for decades, though, the Europeans wanted direct control of Africa’s natural resources. In addition, these countries aimed to “develop and civilise Africa”, according to documents from that period.

Thus began the mad “Scramble for Africa”, as it would later be called. Great Britain, Portugal, France, Germany, and King Leopold II of Belgium began sending scouts to secure trade and sovereignty treaties with local leaders, buying or simply staking flags and laying claim to vast expanses of territory crisscrossing the continent rich with resources from palm oil to rubber.

Squabbles soon erupted in Europe over who “owned” what. The French, for example, clashed with Britain over several West African territories, and again with King Leopold over Central African regions.

To avoid an all-out conflict between the rival European nations, all stakeholders agreed to a meeting in Berlin, Germany in 1884-1885 to set out common terms and manage the colonisation process.

No African nations were invited or represented.

The Berlin Conference

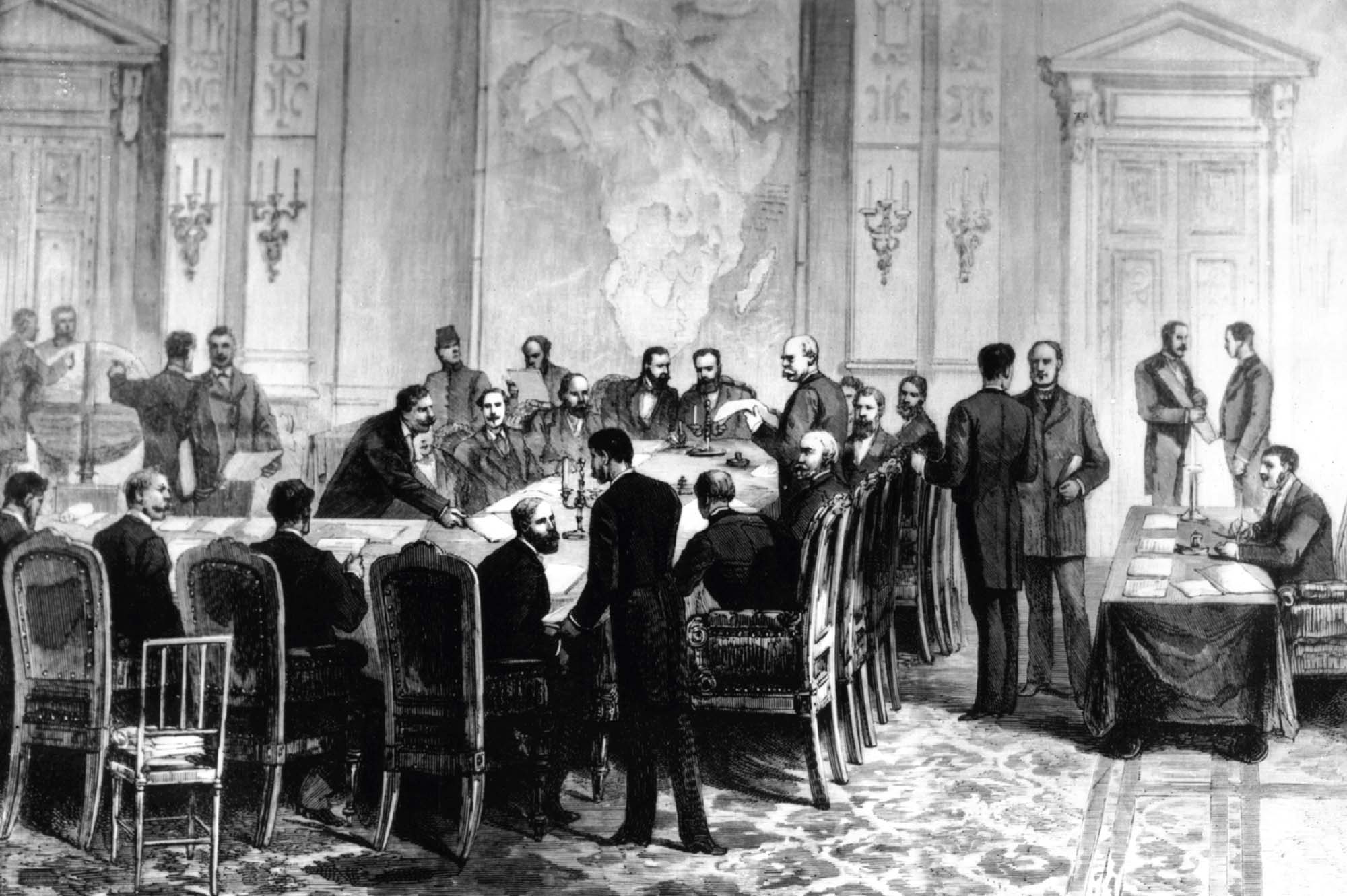

On November 15, 1884, Otto von Bismarck, chancellor of the newly-created German Empire, opened the Conference of Berlin on West Africa at his official residence in the city, 77 William Street. For months leading up to that, French officials, in missives to Bismarck, had raised worries about Britain’s gains, especially its control of Egypt and the Suez Canal transport route. Germany, too, was worried about conflicting areas with the British, such as Cameroon.

The Bismarck-led talks lasted from November 15, 1884 until February 26, 1885. On the agenda was the clear mapping and agreement of who owned which area. Regions of tax-free commerce and free navigation, particularly in the Congo and Niger River basins, were also to be clarified.

The relatively free competition which had characterised capitalist development in the 1860s was supplanted by an enormous concentration of production in the hands of factory owners, bankers and big business. The age of finance capital had arrived. Colonialism, which had been on the wane, underwent an explosive revival as the need arose for new areas in which to invest and the establishment of protected markets to consume the vast output of commodities produced by the advanced capitalist countries.

Ambassadors and diplomats from 14 countries were present at the meeting.

Four of them – France, Germany, Britain, and Portugal – already controlled most of the African territory and were thus the chief stakeholders. Belgium’s King Leopold also sent emissaries to secure recognition of the “International Congo Society”, an association formed to establish his personal control of the Congo Basin.

No African leader was present. A request by the Sultan of Zanzibar to attend was dismissed.

Aside from those were nine other countries, most of whom would end up leaving the conference with no territory at all. They were Austria, Hungary, Denmark, Russia, Italy, Sweden, Norway, Spain, Netherlands, Ottoman Empire (Turkey) and the United States of America.

Outcome of the Berlin Conference

Over three months of haggling, European leaders signed and ratified a General Act of 38 clauses that legalised and sealed the partition of Africa. The US ended up not signing the treaty because domestic politics at the time began to take an anti-imperialist turn.

The colonising nations drew up a ragged patchwork of new African colonies, superimposed on existing “native” nations. However, many of the actual borders recognised today would be finalised at bilateral events after the conference, and following World War I (1914-1918) when the Ottoman and German Empires fell and lost their territories.

In addition, the General Act internationalised free trade on the Congo and Niger River basins. It also recognised King Leopold’s International Congo Society which was controversial because some questioned its private property status. However, Leopold claimed he was carrying out humanitarian work. Areas that ended up under Leopold, known as the Congo Free State, would suffer some of the worst brutalities of colonisation, with hundreds of thousands worked to death on rubber plantations, or punished with limb amputations.

Finally, the Act bound all parties to protect the “native tribes … their moral and material wellbeing”, as well as further suppress the Slave Trade which was officially abolished in 1807/1808, but which was still ongoing illegally. It also stated that merely staking flags on newly acquired territory would not be grounds for ownership, but that “effective occupation” meant successfully establishing administrative colonies in the regions.

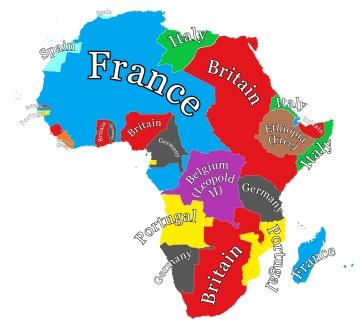

Who ‘got’ which territories?

Western “ownership” of African territories was not finalized at the conference, but after several bilateral events that followed. Liberia was the only country not partitioned because it had gained independence from the US. Ethiopia was briefly invaded by Italy, but resisted colonisation for the most part. After the German and Ottoman empires fell following World War I, a map closer to what we now know as Africa would emerge.

France got French West Africa (Senegal), French Sudan (Mali), Upper Volta (Burkina Faso), Mauritania, Federation of French Equatorial Africa (Gabon, Republic of the Congo, Chad, Central African Republic), French East Africa (Djibouti), French Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire, Dahomey (Benin), Niger, Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco and Libya.

Britain got Cape Colony (South Africa), Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), Bechuanaland Protectorate (Botswana), British East Africa (Kenya), Northern Rhodesia (Zambia), Nyasaland (Malawi), Royal Niger Company Territories (Nigeria), Gold Coast (Ghana), Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (Sudan), Egypt, and British Somaliland (Somaliland).

Portugal got Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique), Angola, Portuguese Guinea (Guinea-Bissau) and Cape Verde while Germany got German Southwest Africa (Namibia), German East Africa (Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi), German Kamerun (Cameroon) and Togoland (Togo).

Belgium and Spain both got one territory each in Congo Free State (Democratic Republic of the Congo) and Equatorial Guinea (Rio Muni), while Italy got Italian Somaliland (Somalia) and Eritrea.

Historians have pointed out that unlike what is widely believed, the Berlin Conference did not kick-start the colonisation process; instead, it accelerated it.

While only about 20 percent of Africa – mainly the coastal parts of the continent – had already been staked by European powers before the conference, by 1890, five years after it, about 90 percent of African territory was colonised, including inland nations. Colonialists were believed to have largely disregarded previous alignments and grouped peoples of different cultures and languages together, even groups that were never friendly towards each other.

Resources were looted and culture and resistance were subjugated.

Even after African leaders successfully fought for independence and most countries became liberated between the 1950s and 1970s, building free nations was difficult due to the damage of colonisation, researchers say. Because of colonialism, Africa acquired a legacy of political fragmentation that could neither be eliminated nor made to operate satisfactorily.

Following independence, civil wars broke out across the continent, and in many instances, caused armies to take power, for example in Nigeria and Ghana. Political theorists link that to the fact that most groups were forced to work together for the first time, causing conflict.

Meanwhile, military governments would continue to rule many countries for years, stunting political and economic development in ways that are still obvious today, scholars say. Former colonies such as Mali and Burkina Faso, both led by the military, have now turned against France because of perceived political interference they say is an example of neo-colonialism.

On the 140th anniversary of the Berlin Conference, these trends underscore the need for renewed attention to an event whose consequences for Africa have left a jarring scar on the entire world.